by Noelle Stapinsky

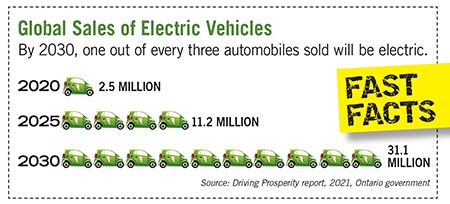

What Canada’s auto industry, and the shops supplying it, must do to become a fiercely innovative, advanced manufacturing powerhouse for electric vehicles

It would be an understatement to say that Canada’s automotive suppliers and manufacturers have merely shifted gears to take on the new zero emission automotive landscape. They’ve been actively focused on navigating new opportunities, readying themselves for the shift away from traditional production and processes, developing and working with new materials, and, of course, answering every call to the table.

Certainly, the pandemic showcased just how diverse and pivot-ready the industry is—retooling and jumping into personal protective equipment production—but it also accelerated the investment in automation and inspired a complete overhaul in the way business is conducted. Even the tiered supply structure has dramatically changed, opening the doors to a plethora of opportunities and challenges for all shops, big and small.

Over the next decade, automotive manufacturing will have to adjust to market demands that include a challenging array of powertrain options. The options will range from electric battery and hydrogen fuel cell-powered vehicles to traditional gas and diesel-powered vehicles to hybrid vehicles which combine electric power with fossil fuels. Somehow for the traditional OEMs all these vehicles will have to run on the same assembly line, but production will have to be scaled to meet regional market demands which are anticipated to vary widely to 2035.

Such increased complexity will require significant changes in manufacturing and the only way to move forward is through flexibility, advises Joerg Reger, managing director, Auto OEM, for ABB Automotive.

Lighter, stronger, more complex

Lighter, stronger, more complex

“It’s not just about light weighting anymore. There’s a lot more to understand,” says Mike Bilton, tooling and automation group chair for the Automotive Parts Manufacturers’ Association (APMA) and Select Tool Inc.’s manager of business development. “Before it was just the exterior segment that was shifting from traditional ABS or thermoplastics to different types of materials. It’s no longer just the exterior components, it’s now the entire vehicle that’s being optimized in terms of geometry and structure and what materials can be swapped out with carbon fiber reinforced plastics, for example, or some form of woven advanced material, which turns out to be structurally just as strong as its predecessor, but maybe half the density or half the weight or more.”

The switch from internal combustion engines is where Bilton says we will see the greatest swap out of legacy style engine parts for battery assemblies, battery packs and smaller drivetrain systems.

“As far as light weighting goes, yes we are seeing a lot less componentry—up to 10 or 20 per cent of a traditional vehicle. It will depend on what parts will be going into the vehicle, which could be a plastic injection molded type of resin, a 3D-printed part with a different density plastic, or if it’s created by way of autoclave tooling, for example, where fabric and plastics are bonded together to create a light, yet strong and flexible part,” he says.

For job shops that have traditionally built exterior, under-hood or even interior parts, Bilton says now is the time to be open and realistic: “Do some experimentation, invest in research and development and new equipment to work with these new materials. And don’t be afraid to form a relationship or partnership with a supplier or even a competitor and work together.”

Strength in Unity

Strength in Unity

Bilton adds that what he’s noticing now more than ever is that suppliers are stepping up and offering partnerships or partnership strategies to relieve the OEMs of doing all the hard work. “Material groups at the OEM level are typically the ones that ignite possible alternatives,” says Bilton. “Now, they’ve sort of shifted that over and said ‘our suppliers are the real experts, let’s have them innovate, accelerate and co-develop with us. We’ll provide the specs and let the suppliers blaze a new trail in some new crazy direction’.”

Another big disruptor is an uprising in more non-traditional OEMs, which is driving this change in supply structure and inspiring more partnerships within the industry.

“You have your traditional OEMs like Ford, General Motors, Toyota, Honda, etc., but then you have new players in the market, such as Kia, and then there’s non-traditional automakers that are now fueling the demand,” says Jonathon Azzopardi, president and CEO of Laval International and interim chair of the Canadian Association of Moldmakers (CAMM). “There’s Lordstown, Waymo, which is Google, Apple and Amazon that are starting to play in the industry. These non-traditional OEMs are complicating the situation, but also adding fuel to the BEV and connected vehicle [market].”

Azzopardi continues, “it’s important that we understand the entire landscape of the automotive industry and how it’s changing right before us. The days when we just had the Big Three, as we called them, is no longer the case. We are now, as a supplier, working with many different OEMs and they’re going directly to the Tier 2 and Tier 3s because they’ve broken free of the traditional supply chain structure. It’s literally changing how we do business, which is creating opportunities, but also some challenges too. I’m working directly with Tesla and Lordstown, for example. And because the Tier 1 suppliers are so busy, the OEMs have downloaded all of this responsibility down the chain. It’s for parts, but also sensors and other technologies going into these vehicles.”

At Laval, Azzopardi says they’ve brought on a design staff and achieved higher certifications. “We are IATF certified now, where in the past ISO was acceptable because we just did tooling. Now, because of these new opportunities, we are a design company, we create the tooling, and we’re part responsible. We’re also doing prototyping and low-volume production to get these non-traditional OEMs off the ground. Being design responsible, tool responsible and part responsible might not sound like a lot, but it literally adds thousands of new potential liabilities to your list. As an owner, I’m excited because it’s more opportunity and it’s making us a better company. But not every company is prepared for that type of responsibility.”

Indeed, the biggest challenge for fabricators or job shops in general will be human resources. And this is why partnering will become pivotal to stay in the game and remain competitive.

“If you’re a shop producing 1,500 aluminum stamped parts a week, for example, you can partner with a plastic parts supplier and work together to co-develop, through design and product development, to integrate advanced materials with a lighter geometry and thinner wall sections,” suggests Bilton. “If you change the way you do things, it changes what you make. And sometimes it’s not a large investment after all. It just means you’ve changed the way you see a product, manipulated the specs and worked in tandem with your OEM customer or supplier. It’s really a race to be the supplier of choice by way of driving sales through engineering. What we’re seeing now is a high competitiveness or joint competitiveness between supplier, partner and customers. And that’s what OEMs are looking for—suppliers to have a joint partnership to share and combine competitiveness, and to be able to reduce piece price, manipulate throughput, while advanced technology improves quality and timing.”

Another known challenge, and this is true for all industries, is the supply chain crisis. Prices of raw materials have surged, lead times are longer, and depending on where materials or equipment are sourced, deliveries can take months or get held up in transit. And, of course, the hot topic for the automotive world has been about the semiconductor chip shortage, which has halted OEM production for many vehicle segments.

As Canadian Manufacturers & Exporters president and CEO Dennis Darby told the recent National Supply Chain Summit convened by the federal government, manufacturers have been dealing with supply chain pressures for too long.

“Bottom line, there are many things Canada must do to tackle the supply chain problem. But it all starts with a firm commitment from government to work with industry to resolve these challenges,” Darby said.

In SHOP’s Business Outlook feature published in November 2021, Bilton said that automakers were starting to talk about manufacturing their own chips in-house. “Look what some have done. They’re planning on full-volume production because they’re making their own chips. That’s how they’re getting around the shortage and everyone else is following suit.”

Upstart Tesla took a lead role in this approach, and it paid off. Tesla managed to sell almost twice the number of vehicles last year than it did in 2020 because it was able to operate relatively unhindered by the shortage of computer chips faced by the traditional car manufacturers. First, Tesla appeared to do a better job of forecasting demand than its competitors after the initial dramatic drop in car sales caused by the Covid 19 pandemic. And when Tesla couldn’t get the computer chips required to meet the new demand, it took what it had available and rewrote the software to suit its needs. Larger car manufacturers couldn’t do that because they had relied on outside suppliers for their software and hardware needs.

Support for innovation in Canada is coming from all angles. The Big Three, as well as the provincial and federal governments, announced financial commitments, which place Ontario on the map as a leader in electric vehicle technologies. Next Generation Manufacturing Canada (NGen), the industry-led organization behind Canada’s Advanced Manufacturing Supercluster, recently announced a $20 million investment in R&D projects for battery and fuel cell innovation, which is matched by industry investment to total $40 million for a program called the Automotive Zero-Emissions Manufacturing Challenge.

And the APMA’s Project Arrow is an all-Canadian effort, full-build, zero-emission concept vehicle which is expected to be unveiled by the end of this year. “This is where we’re allowing our suppliers to showcase their technologies and try something different,” says Bilton. “We’ve been called to the table and the APMA, our members and our suppliers for Team Canada are all looking at what we can do to diversify our products and processes.”

APMA president Flavio Volpe emphasized Canada must take a leading role not only in building the vehicle of the future but also in how to power it.

“If we want to be leaders in this space, we need to find a way to make batteries at home. It’s going to cost money but if we don’t do it, someone else will,” Volpe told those in attendance at the recent Canadian Manufacturing Technology Show. “If you put a shovel in the ground in Northern Ontario, Alberta, and Saskatchewan, you’ll find all the lithium needed.”

His message to the Canadian automotive industry and its suppliers was both challenging and undeniably exciting: “We have everything in this country. We do the tooling, raw material manipulation, design engineering, supply of all kinds of different assemblies, and build vehicles. We can make everything in this country for a vehicle. And then it begs the question, why don’t we?”

Canada’s industry has already recognized the strength in partnerships and, according to Bilton, the conversations at the table between the public and private sectors are now more prevalent than ever.

As Volpe put it in his closing remark at CMTS: Are we ready for tomorrow? SMT