by Kip Hanson

Looking for a high-speed machining centre? You won’t have to look far. That’s because, in today’s world, practically all of them qualify as “high speed,” at least by yesterday’s standards. And best of all, they’re only getting faster.

When asked to define the term “high-speed machining,” Peter Sheridan’s response is quick and to the point. “It has become a vague term and no longer has any real meaning.” Coming from the technical product manager at Ferro Technique, a distributor of machine tools throughout eastern Canada, his answer was surprising. In some ways, it was also dismaying.

Gone are the glory days of high-performance carbide end mills ripping through aircraft components and die cavities at hundreds of inches per minute? No more measuring machine tool performance based on its look-ahead capabilities, or arguing over how much RPM it takes to consider a spindle “high-speed”?

Looking ahead

Looking ahead

Not at all. These attributes remain every bit as important as the day that high-speed machining (HSM), high-efficiency machining (HEM), and high-performance machining (HPM) were first introduced; it’s just that most modern machine tools can now leap the bar that was set when these terms were all the rage.

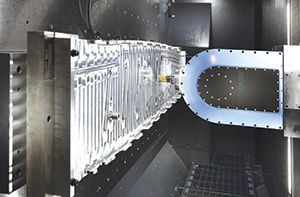

Sheridan notes that most CNC machine tools today have linear guideways, a necessity for high-speed machining with its extremely fast feedrates and axis motions. Compare that to two decades ago, when arguments over the relative merits of so-called “box ways” or hydrostatic guideways and their linear counterparts were common. “Box way machines are still available, but they’re few and far between,” he says. “Practically everyone has gone linear, which is far better suited to moving quickly.”

And the look-ahead capabilities and spindle speeds just mentioned? As anyone who’s shopped recently for a new CNC machine tool can attest, such features are also becoming standard. For example, many of the models in Ferro Technique’s flagship line of Doosan machining centres boast 15,000 to 18,000 RPM spindles. For that matter, even multitasking CNC lathes are edging into “high-speed” territory with 12,000 RPM milling capabilities.

A similar claim can be made for look-ahead, which in simplistic terms, allows the machine’s servo control system to “peek around the corner” at whatever interpolation demands are coming its way. “Ten years ago, advanced control features like FANUC’s AICC [AI Contour Control II] and High-Speed Processing were options you had to pay for,” said Sheridan. “With Doosan, they’ve since become standard, and I’m sure the other machine and control builders are including similar features in their products.”

Big changes afoot

Big changes afoot

The reason for all this? The machining world has changed. It’s no longer necessary (or even preferred) to hog out parts with high-speed steel (HSS) corncob cutters, or slab off the tops of workpieces with face mills the size of Frisbees. Light depths of radial cut and aggressive feedrates have become the norm, and according to applications and engineering manager Ian Candolini, also with Ferro Technique, you can give much of the credit (or place much of the blame) on cutting tool manufacturers and CAM developers.

“Cutting tool manufacturers have developed some very advanced products over the past decade or two,” he said. “The coatings, grades, and geometries available now are light years ahead of what we once had, so it’s only natural that productivity-minded machine shops want to take advantage of it. At the same time, the CAM folks have delivered toolpaths that leverage these tools. Trochoidal cutting routines that utilize the chip thinning effect allow shops to take full-length cuts at feed rates that used to be impossible, resulting in far higher metal removal rates, better tool life, and less wear and tear on the machine.”

Machine tool builders have responded with CNC machinery that accommodates the industry’s shift to more effective machining practices, he suggested. The problem is that some shops haven’t gotten the message. Says Candolini: “It’s hard for a lot of people to wrap their head around the changes, especially the veteran machinists who grew up using conventional metal removal techniques. Even when you show people how much faster it is

with the new technology, some will still put up red flags and say, ‘No, you’re wrong. It’s not going to work that way.’”

Sheridan seconds this last point. “We had a customer once who bought a horizontal machining centre. It was a beautiful machine—linear guideways, high RPM spindle, top-of-the-line control, the whole package. And he refused to run any modern cutting tools. He only wanted to buy high-speed steel end mills and run them at 200 RPM going three inches a minute, just like he’d been doing for decades. But the machine wasn’t designed for that, so it would vibrate, stall out, break cutters, and scrap out parts. He put his foot down, though. ‘My way is the right way, damn it!’. Unfortunately, he’s now out of business.”

Forward, Ho!

There’s no going back, he adds. Machinists living in the past will find it increasingly difficult to find the tooling they are accustomed to using. For example, do a quick search for “HSS end mills” and you’ll see that many cutting tool manufacturers have stopped producing them. HSS drills, though still prevalent, can’t be far behind. Similarly, the geared headstock, box-way lathes and machining centres of yore are slowly fading out of existence.

What to do about it? The answer is obvious: embrace new manufacturing technology wherever possible. It won’t necessarily be easy, however. It’s one thing to suggest that shops adopt high-speed machining practices and the tooling that goes with it, but this approach won’t work with the legacy equipment just described. This means shops stuck with a mix of the old and new (as most of them are) must take two distinct approaches to part processing—one for the vintage machine tools, and another for the more modern equipment.

The good news is that the latter approach will soon take precedence, pushing out the old like a worn set of white-walled tires. Shops will produce more parts in less time, tooling costs will go down, quality levels and profitability alike will go up. This new age of machining mentality extends beyond “high-speed” to include five-axis machining and mill-turn/multi-tasking centres. For such equipment, you can add increased flexibility and set-up time reduction to the benefits listed just now.

“Machining in North America is getting to the point where you have to adopt new technology or you simply won’t be successful,” says Sheridan. “Companies that own a handful of 6,000-rpm, three-axis vertical mills don’t have to worry about competition from Asia—they’re competing with the shop down the street that invested in a horizontal machining centre last year, one with a pallet pool and 20,000 RPM spindle. That shop is flying through material and they’re doing it 24 hours a day, while you’re sitting there flipping through parts one operation at a time, using the same vises and cutting tools you were using twenty years ago. Keep doing it that way and the phone’s eventually going to stop ringing.” SMT