by Kip Hanson

For many applications, deep hole drills are a cost effective and productive alternative to gundrilling

Most industry experts agree on the merits of gundrilling, a technology that machines precision holes hundreds of diameters deep with smooth walls and unparalleled straightness. As the name implies, gundrills were invented as a way to make more accurate gun barrels than was possible with the cast or forged versions of that time. As a rule, the process uses a counter-rotating, single fluted cutting tool with a tubular drill body, supported by bushings along its length. This keeps the drill running straight and true, and minimizes vibration.

It’s a simple yet elegant way to make accurate holes, using fairly inexpensive tools in virtually unlimited lengths. The only problem is, it’s relatively slow compared to conventional holemaking techniques, which often boast double the feedrate, and can sometimes drill five to six times faster.

Hours to minutes

“A number of our customers come to us looking for alternatives to gundrilling, primarily because of long cycle times,” says Sam Matsumoto, application engineer at OSG Canada Ltd, Burlington, ON. “We have one customer who reduced their total cycle time from hours to minutes by switching to one of our WDO drills.”

Google “deep hole drills” and you’ll come across a wide variety of solid carbide, coolant-fed drills in the 3 mm to 12 mm diameter range (0.125 to 0.500 in.), with lengths up to 30 times diameter (30XD) or greater. OSG’s Exocarb WDO falls into this category. Matsumoto says it’s important to manage tool runout on any drilling operation, but especially so as hole depths exceed ten times the drill diameter. He recommends shrinkfit or hydraulic toolholders, or a very high quality ER-style collet on shallower holes.

“The less runout the better,” says Matsumoto. “Without a precision holder and very accurate alignment, tools are far more prone to break during deep hole drilling operations. They make a night and day difference.”

Avoiding tool breakage is an obvious goal in any metalworking operation. Matsumoto warns customers to keep an eye on flute and margin wear, replacing tools before failure can occur, and to always send drills back for re-sharpening. “A further way to reduce operating cost and maintain productivity is to have a drill reconditioned to factory specifications. Sharpening long drills can be a complex process. The point has to be thinned properly, the angles have to be correct, and if it’s not done right you’ll end up with chatter or drill walk; worst case, it will break within a few holes.”

Drilling to the max

Komet of America Inc. is another provider of coolant fed, solid carbide deep hole drills. Business development manager Michael Hunter says the company’s KUB Drillmax XL line has a four-facet, double margin geometry on drills longer than 5XD. This helps guide the tool, and provides a burnishing effect that improves hole surface finish.

“We can go up to 30XD standard and offer specials for aluminum drilling up to 40XD,” he says. “Solid carbide twist drills are an excellent solution in this range, but after that you get into gundrilling territory, and options become very limited.”

“We can go up to 30XD standard and offer specials for aluminum drilling up to 40XD,” he says. “Solid carbide twist drills are an excellent solution in this range, but after that you get into gundrilling territory, and options become very limited.”

Hunter agrees with gripping drills in shrinkfit or hydraulic chucks, and adds that the slightest amount of tool runout on solid carbide drills can create a dangerous situation, magnifying inertial forces enough to instantly snap the drill and possibly send it flying across the shop. This is one of the reasons he recommends using a pilot hole to contain the drill tip, and only engage the spindle once the drill is actually in the hole.

“Pilot holes are a good idea in any deep hole application,” he says. “Use a stubby drill the same size to make a hole three diameter deeps, then go in with the longer drill rotating at a few hundred rpm, and then increase to the recommended operating speed. This helps guide the drill and keeps it from hitting the edge of the hole if there’s any droop, which can sometimes happen on a horizontal machining cente or lathe. We also strongly recommend high pressure coolant, preferably up around 60 bar (870 psi), but don’t turn it on until the drill is in the hole, otherwise you can get some whip and vibration, especially on very small drills.”

Employ the right drilling strategy

“I think a lot of people don’t apply the correct drilling strategy on deep holes,” says Luke Pollock, product manager for Walter Tools, West Waukesha, WI. “We recommend using a true pilot drill with a point angle 10° greater than the secondary drill. It’s not just a shorter version of a standard drill. The wider point helps avoid chatter when the longer drill first makes contact. And for very deep holes, or tough materials, we often suggest using an interim drill, to get you from the initial pilot hole to maybe 16XD, and then finish with the full length drill. This splits the work up between the tools, and let’s you do more metal removal with a less expensive tool.”

Walter’s newest drill line is the DC170, which has a series of spiral grooves behind the drill point designed to provide better lubrication and make the tool stronger than comparable drills.

“There’s substantially more surface area at the drill tip making contact with the walls,” Pollock says. “This supports the tool and reduces chatter and deflection, something that becomes very evident when you’re going through interruptions or uneven exits where a traditional drill might push off to the side. And the greater mass allows for much higher feedrates. It’s a unique design.”

Like OSG’s Matsumoto, Pollock says the drills should be returned to the manufacturer for reconditioning. To those customers that complain over the price of solid carbide–a 12 mm (0.500 in.) long length solid carbide drill, for example, can easily cost $500 or more (sometimes far more)–Pollock says that compared to gun drilling, long length twist drills are often far more cost effective.

Like OSG’s Matsumoto, Pollock says the drills should be returned to the manufacturer for reconditioning. To those customers that complain over the price of solid carbide–a 12 mm (0.500 in.) long length solid carbide drill, for example, can easily cost $500 or more (sometimes far more)–Pollock says that compared to gun drilling, long length twist drills are often far more cost effective.

“Gundrilling offers excellent straightness and size control,” he says. “The problem is the speed. With most gun drills, you might be limited to a few inches a minute. With a tool like the DC170, we can feed through cast iron at seventy inches a minute. When you roll in the time savings against the machine burden rate, it becomes a no-brainer, regardless of tooling cost.”

Tooling inventory

John Mitchell, general manager for Tungaloy America in Canada agrees with most of what’s been said here, except for one thing: tooling inventory. “With a solid carbide drill, you have to send it out for regrind and wait for it to come back. That probably takes one week or longer. So if you’re running a continuous job that gets four hours of cutting per drill, that means purchasing at least ten very expensive tools for each shift. With an indexable drill, all you need is the drill body, a backup tool, and a box or two of inserts. It’s far less expensive.”

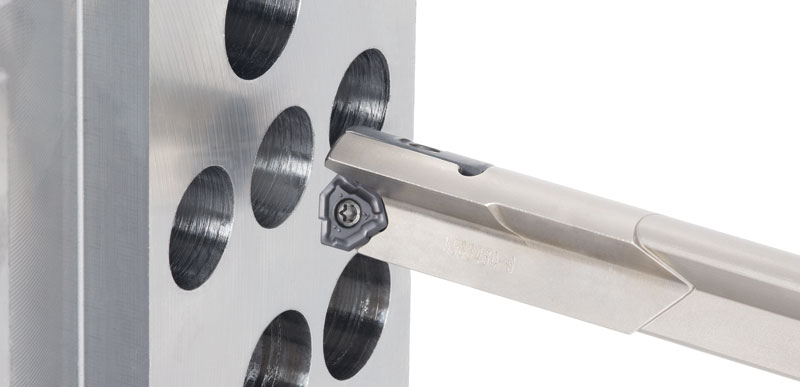

Similar to a gundrill, the TungDrillTri is a single flute drill with a straight chip gullet. It has an indexable carbide insert with three serrated cutting edges, opposite of which sits a pair of replaceable carbide guide pads that serve to support the drill while burnishing the hole walls, giving it the ability to achieve IT10 class accuracy. The drill comes standard in 16 to 28 mm diameters (0.629 to 1.102 in.) and lengths up to 25XD, although Mitchell says specials up to 90XD are available on some sizes.

“The insert serrations on the TungDrillTri solve one of the biggest problems with deep hole drilling, chip evacuation,” he says. “There’s a lot of science behind the insert. The cutting edge has a positive cutting action and is designed to break the chip into small pieces, which are very easy to flush. There’s also a wiper flat on the inside edge that helps guide the drill. Compared to solid carbide, these drills are easier to operate. There’s no need to adjust tool length after regrind, just replace the insert and go. It’s a good solution for a number of applications.” SMT